A few minutes into the ersatz 1991 “Meaning of Life” informercial for Phillips CD-i, the omniabsent salesgod speaking to our cheerful white dad stand-in, Phil, gets a little rude.

Phil is teased that perhaps his hand-eye co-ordination isn’t up to battling through the game Zelda: The Faces of Evil. Instead, Phil is bamboozled in the traditional sense through a series of conceptual sales pitches as distractions from his request for help from the game. All the other wonders that the Phillips CD-i would offer him were far more important to highlight.

The Promise Then Made

The Phillips CD-i was one of many pieces of corporate flotsam attempting to materialise the phantasm of the ‘information superhighway’. This diaphanous linguistic parlour trick was the promise made. The promise was to those without computers, or one they didn’t care about, that a bunch of different problems were all going to get solved at once. The actual resulting mid-90s internet of bulky and brutish little corporate box websites, complex Geocities addresses, RealPlayer errors and Netscape Navigator animated logo guided meditations ran roughshod over the Internet that was already there - IRC, Usenet and BBS networks full of fecundity and.. people.

Phillips didn’t really get to shape as much of the future as they wanted. Technologies remained stubbornly disconnected. Fundamentally, we didn’t live like their concept videos. The real Phil didn’t want to switch from playing a Zelda game to browsing an encyclopedia to a trivia night with the kids. The real Phil wanted to pirate movies. He wanted to yell at strangers online about tax. He wanted to hock off his terrible guitars.

By the time the term ‘information superhighway’ had cast its magic in the middle of the decade, people the world over instinctually (and correctly) saw the internet as full of advertisers, grifters and weirdos. It was, and would remain, a perennial struggle against bullshit.

Over and over since then, the ‘metaverse’ conceit replaced the ‘information superhighway’ as the predominant symbol of the Bullshit-to-Come. There were symbolic attempts to make it roughly egalitarian in keeping with the old internet (VRML, etc), and a string of pro-corporate promised lands (Second Life, Playstation Home, etc) too numerous to catalogue. Where the ‘information superhighway’ presaged an internet for sad dads in the 1990s, the ‘metaverse’ presages a brutally uncomfortable family road trip now that a generation has passed.

The Shambolic Deliverance

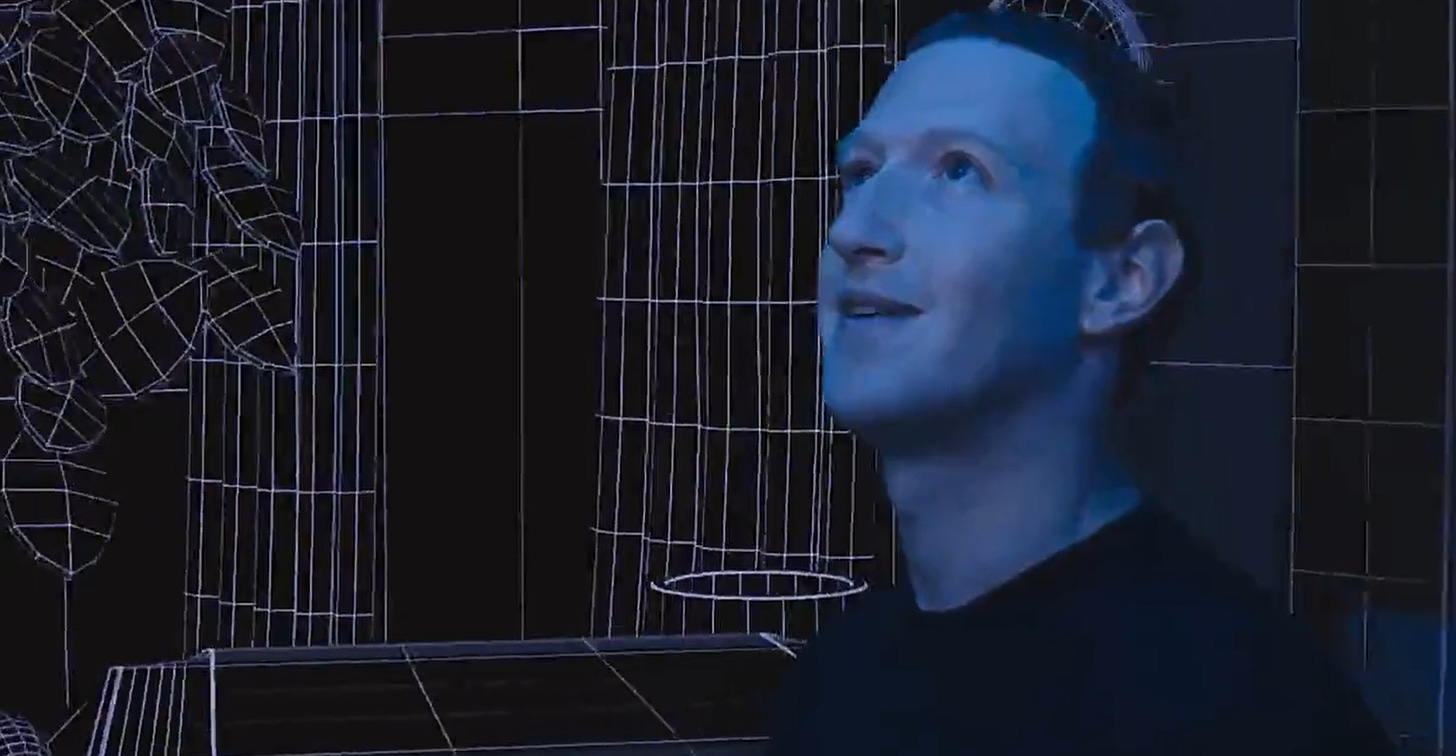

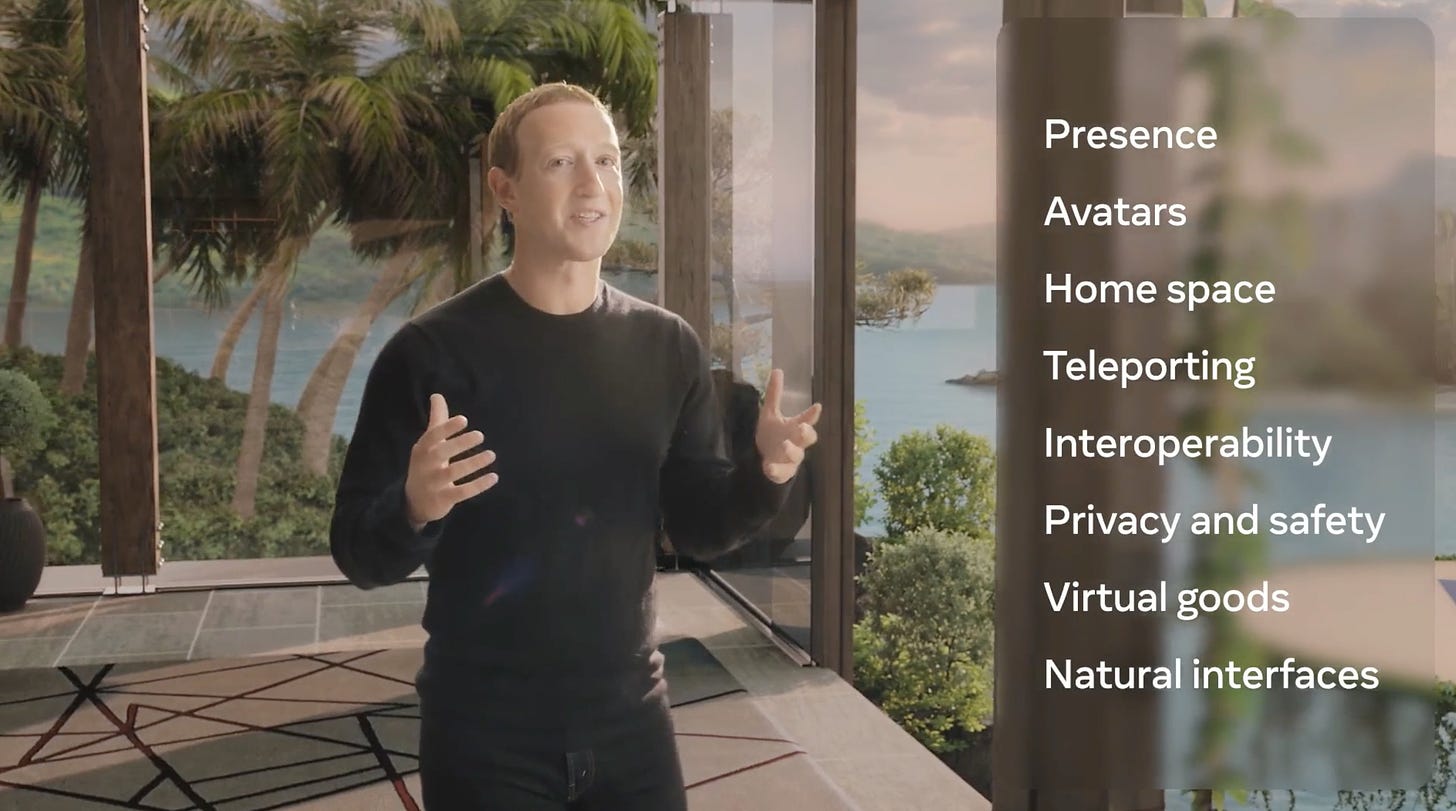

A naturally-occurring, deep seated glee overcomes you as you watch Mark Zuckerberg waffle through his vision of the future. One where you have to wear a device on your head to have a Zoom meeting, after two years where the radical frictions of working online are reshaping commerce.

One where you can apparently ‘tip’ a ‘3d street artist’ to keep a 20 second animation going for another 10 seconds.

“It doesn’t exist and it doesn’t make sense” pretty much covers it. But throughout the Facebook/Meta video, you’re faced with use cases that similarly don’t exist and don’t make sense. You’re told to feel awe when problems you don’t have are solved in ways you don’t care about, to resolutions which don’t apply to you. This is not exclusive to Facebook or to tech generally, but there’s a special breed of fantasy that emerges in the concept video. You always watch the reflected delight in the face of the stand-in. You always follow the hands of the salesperson to the list of minutiae.

Anybody who has seen a videogame console announcement or any of the myriad videogame conferences will have experienced a similar vertiginous gut-drop. Flustering promises all wrapped around sad dad monologues begging to be taken seriously by the people who will decide whether or not their gamble will pay off.

These videos follow a format that is generations old. Through the 50s and 60s, what would become the informercial developed alongside broadcast technology, drawing down from its antecedents in print and radio. What they’ve kept down the generations mutates only so much as their vision of the forever-future needs to. Doesn’t Zuckerberg’s glass window refuge remind you of a mid-century modern vibe? Isn’t it weird that his metaverse fireplace is just basically a 70s Malm number with worse fire animation than After Dark screensavers had back in 1991? Isn’t it depressing to see exiled UK sellout Nick Clegg imprisoned in a colour-coded room with floor-to-ceiling bookcases but with all his actual books confiscated?

They’re Not Coming

Brad Esposito of Vice did God’s work by asking some teenagers (you know, the people who will be the prime audience of this technological wonderland in 4-7 years time) what they thought of this latest P.T. Barnumification of the future. They aren’t using Facebook, and they’re not going to. The entire language of concepts that the metaverse uses - ersatz, happenstance ‘hangouts’, seamless and endless work meetings - don’t apply to anybody under 40 years old. That universe is flickering and fading. It’s a universe overseen by sweaty, overkeen uncles who think they’ve nailed the Christmas gift by getting what they wanted at the same age.

Facebook can at least be given credit for understanding their brand is, for most people, ‘a corrupt and hateful cop who is killing my grandparents slowly but surely’, but zero credit for attempting to fantasise their way out of the future they irreversibly destroyed. From here, you just know you’ll get more and more of these shameless showcases. Meta, like so many before them, are now a concept video company.

Among the many missing parts of the future in their concept video was any mention of reading or consuming local news. This industry, more than any other, was executed and buried by Facebook’s tactical war on the rest of the internet, a death shroud stained with a promise they’d survive if they made content the way Facebook wanted - video first. Perhaps as they make their own fateful pivot to video, they can see what it’s like to plan for blue skies with no idea what’s happening on the ground.